You may hear the term “walking pneumonia” and imagine something less serious, perhaps even trivial. While it’s true that it’s generally a less severe form than some other types of pneumonia, it’s still a lung infection that requires proper care and attention. I frequently have patients ask, “Doc, I’ve been feeling rundown, but I’m still managing to go to work… could it be walking pneumonia?” It’s a valid question, and understanding this condition is the crucial first step toward feeling better.

Let’s break down exactly what walking pneumonia is, who tends to get it, what symptoms to look out for, and how we, as healthcare professionals, diagnose and treat it.

Defining Walking Pneumonia: More Than Just a Bad Cold

So, what is walking pneumonia, precisely? At its core, walking pneumonia is an infection affecting the lungs, much like classic pneumonia. However, the term “walking” arises because the symptoms are often mild enough that individuals can continue their daily routines – walking around, going to work or school – without being completely bedridden. It’s also commonly known by its medical term: atypical pneumonia.

What Causes Walking Pneumonia?

While more severe forms of pneumonia are often caused by bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae, walking pneumonia frequently stems from different culprits:

- Bacteria: The most frequent bacterial cause is Mycoplasma pneumoniae. This tiny bacterium is unique because it lacks a cell wall, which influences which antibiotics are effective against it. Other bacteria can also be responsible.

- Viruses: Various common respiratory viruses can lead to symptoms consistent with walking pneumonia. It’s important to remember that viral pneumonia doesn’t respond to antibiotics, highlighting why determining the likely cause is key.

- Fungi (Molds): Less commonly, certain fungi can cause atypical pneumonia, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems.

The main takeaway here is that “walking pneumonia” describes a clinical presentation – a milder lung infection – rather than pointing to one specific germ. However, Mycoplasma pneumoniae is the bacterial cause most commonly associated with this condition.

How Does Walking Pneumonia Differ from “Regular” Pneumonia?

This is an important distinction I often clarify for my patients. While both are lung infections involving inflammation and potential fluid or mucus buildup in the air sacs (alveoli), the primary differences lie in severity and typical presentation:

- Severity: Walking pneumonia is generally milder. Classic pneumonia often brings high fevers (101-105°F or 38-40.5°C), significant shortness of breath, sharp chest pain, and frequently necessitates bed rest, sometimes even hospitalization. Walking pneumonia typically involves lower-grade fevers (often below 101°F or 38.5°C) and less debilitating overall symptoms.

- Symptoms: Although there’s overlap, classic pneumonia often produces a “productive” cough (bringing up thick yellow, green, or sometimes bloody mucus). Walking pneumonia more frequently causes a persistent, nagging, dry cough, though sometimes a small amount of whitish mucus may be present.

- Impact: As the name suggests, people with walking pneumonia often feel unwell but can usually continue functioning. Those with classic pneumonia typically feel too sick to carry on with normal activities.

Think of it like the difference between a steady drizzle and a torrential downpour – both involve rain, but the intensity and impact are significantly different.

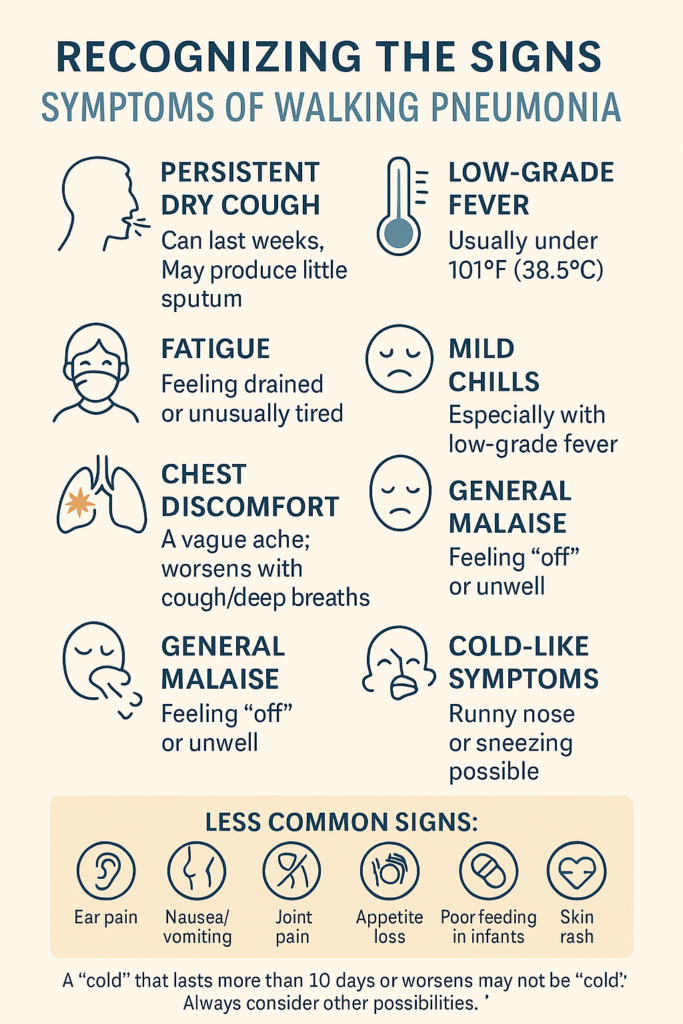

Recognizing the Signs: Symptoms of Walking Pneumonia

One of the challenges with walking pneumonia is that its symptoms can easily mimic a common cold or bronchitis, especially early on. However, the persistence of symptoms and certain characteristic signs should raise suspicion. If a “cold” seems to drag on for more than 7 to 10 days, or if a cough worsens instead of improving, it’s time for us to consider other possibilities.

Symptoms can appear suddenly or develop gradually. Be alert for this combination of signs:

- Persistent Cough: Often the most prominent and longest-lasting symptom. It’s frequently dry or hacking but can occasionally produce small amounts of sputum. This cough can linger for weeks, even after other symptoms have resolved.

- Low-Grade Fever: Typically below 101°F (38.5°C). High fevers are less common than in classic pneumonia.

- Fatigue: Feeling unusually tired, drained, or lacking energy is very common.

- Headache: A dull, persistent headache often accompanies the illness.

- Sore Throat: Frequently one of the first symptoms to appear.

- Mild Chills: May occur, especially alongside the fever.

- Chest Discomfort: Some individuals experience a vague ache or soreness in the chest, sometimes worsened by deep breathing or coughing. Sharp, stabbing pain is less typical than in classic pneumonia.

- General Malaise: A general feeling of being unwell or “off.”

- Other Cold/Flu-like Symptoms: Sneezing and a runny nose can occur.

- Less Common Symptoms: Occasionally, walking pneumonia might present with ear pain, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite (especially in older children and adults), poor feeding (in infants), a skin rash, or even joint pain.

An Important Note for Parents: In children, especially infants, be vigilant for signs of increased work of breathing. This can include fast breathing, grunting sounds with exhalation, or retractions (where the skin pulls in between the ribs, below the ribcage, or in the neck with each breath). These signs require prompt medical attention. Also, be aware that the location of the infection within the lungs can influence symptoms; an infection higher up might cause more obvious breathing difficulty, while one lower down near the abdomen might present primarily with stomach upset.

Who is at Risk for Walking Pneumonia?

While absolutely anyone can contract walking pneumonia, certain groups seem to be more susceptible or may experience more significant illness:

- Age: School-aged children, teenagers, and young adults are frequently affected, especially those in close-contact settings like schools, college dormitories, or military barracks where outbreaks of Mycoplasma pneumoniae can occur. However, very young children (under 2) and older adults (over 65) can also contract it and may face a higher risk of complications.

- Weakened Immune Systems: Individuals with compromised immunity due to illness (like HIV), medications (such as chemotherapy or long-term steroids), or organ transplants are more vulnerable.

- Chronic Lung Diseases: People with pre-existing conditions like asthma, COPD, or emphysema may be more likely to contract pneumonia and potentially experience more severe symptoms.

- Smokers: Smoking damages the lungs’ natural defense mechanisms, increasing the risk of all respiratory infections.

- Crowded Environments: As mentioned, places where people gather in close proximity facilitate the spread of respiratory droplets carrying the germs.

- Inhaled Corticosteroid Use: Regular use, often for managing asthma, might slightly increase susceptibility.

Walking pneumonia tends to be more common during the fall and winter months, aligning with the typical season for respiratory illnesses, though cases certainly occur year-round. Outbreaks, particularly of Mycoplasma, sometimes happen in cycles every few years.

The Contagious Nature of Walking Pneumonia

Yes, walking pneumonia is contagious. The germs responsible (whether bacterial or viral) spread through respiratory droplets released when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks, or even breathes near others. If you inhale these microscopic droplets, you can become infected.

A particularly tricky aspect of Mycoplasma pneumoniae is its potentially long incubation period (the time between exposure and symptom onset) and shedding period. An infected person can actually be contagious for up to 10 days before they even start feeling sick. They remain contagious as long as they have symptoms, which, as mentioned, can sometimes last for several weeks (especially the cough). This extended period of contagiousness, often occurring before a diagnosis is even made, significantly contributes to its spread, particularly within families, schools, and workplaces.

Diagnosis: How Doctors Identify Walking Pneumonia

Diagnosing walking pneumonia involves careful detective work, piecing together clues from your medical history (the story of your illness), a thorough physical examination, and sometimes, specific diagnostic tests.

The Medical History and Physical Exam

When you visit a healthcare provider with symptoms suggesting walking pneumonia, the process typically starts with detailed questions:

- “Can you describe your symptoms?”

- “When did they first begin?”

- “Have your symptoms changed or worsened over time?”

- Have you had a fever? If so, how high?”

- “Are you coughing up any mucus? What does it look like?”

- “Do you have any underlying health conditions I should be aware of?”

- “Has anyone else around you (at home, work, or school) been sick recently?”

Next comes the physical examination. A vital part of this is auscultation – listening intently to your lungs with a stethoscope. We listen carefully over all areas of your chest and back, paying attention to the quality of your breath sounds. While lung sounds can sometimes be completely normal in mild walking pneumonia, we often listen for specific abnormalities:

- Crackles (or rales): Fine, popping sounds that can indicate fluid or inflammation in the small airways.

- Wheezes: Whistling sounds that might suggest narrowed airways.

- Rhonchi: Coarser rattling sounds, often related to mucus in larger airways.

- Diminished breath sounds: Areas where airflow sounds quieter than expected, possibly due to underlying inflammation or fluid.

We will also check your vital signs: temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation (measured easily with a pulse oximeter, a small clip placed on your fingertip).

Diagnostic Tests

Often, especially in straightforward cases, a diagnosis can be confidently made based on your history and the physical exam findings alone. However, if the diagnosis is unclear, if symptoms are unusually severe, or if knowing the specific cause will significantly alter treatment, we might order further tests:

- Chest X-ray: This is a very common imaging test. While it might appear normal in very mild cases, an X-ray can often reveal patchy areas of inflammation or infiltration in the lung tissue. This helps confirm the presence of pneumonia and gives us an idea of its extent. The pattern seen on X-ray in atypical pneumonia can sometimes look different (more diffuse or streaky) compared to classic bacterial pneumonia.

- Blood Tests: A complete blood count (CBC) might show changes in white blood cell levels, sometimes offering clues about infection. Specific blood tests looking for antibodies against Mycoplasma pneumoniae or other potential pathogens can help pinpoint the cause, though these results often take several days. We might also check inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Sputum/Mucus Samples: If you are producing mucus when you cough, a sample can sometimes be collected and sent to the laboratory for analysis. Tests like culture or molecular assays (e.g., PCR) can identify the specific bacterium or virus responsible. However, obtaining an adequate sputum sample can be difficult, especially with the dry cough often characteristic of walking pneumonia. Throat or nasal swabs might also be used in some situations.

Treatment Strategies for Walking Pneumonia

The approach to treatment depends heavily on the suspected or confirmed cause of the infection.

When Antibiotics Are Necessary (Bacterial Causes)

If we strongly suspect or have confirmed a bacterial cause, particularly Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Chlamydophila pneumoniae, then antibiotics are the cornerstone of treatment. Because Mycoplasma lacks a standard cell wall, certain common antibiotics (like penicillin) are ineffective. We typically prescribe antibiotics from classes known to work against these atypical bacteria:

- Macrolides: (e.g., Azithromycin, Clarithromycin) – Often the first choice, generally safe and effective for both children and adults.

- Tetracyclines: (e.g., Doxycycline) – Usually recommended for older children and adults.

- Fluoroquinolones: (e.g., Levofloxacin, Moxifloxacin) – Typically reserved for adults and used if other options aren’t suitable or if the infection is more severe.

It is absolutely critical that if you are prescribed antibiotics, you take the entire course exactly as directed, even if you start feeling significantly better after just a few days. Stopping treatment early can allow the infection to rebound and potentially contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance, making future infections harder to treat. When appropriate, antibiotics usually shorten the duration of illness and reduce the period during which you are contagious to others.

Managing Viral or Other Causes

If the infection is determined to be viral, or if the specific cause remains unclear but symptoms are mild, antibiotics will not help and are therefore not prescribed. In these situations, treatment focuses on supportive care and symptom relief, allowing your body’s own immune system the time and resources it needs to fight off the infection:

- Rest: Even though you might be “walking,” getting adequate rest is crucial for recovery. Listen to your body and don’t push yourself too hard.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of fluids – water, clear broths, herbal teas – especially if you have a fever. Staying well-hydrated helps thin mucus, making it easier to cough up.

- Fever/Pain Relief: Over-the-counter medications like acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) can help manage fever, headache, and chest discomfort. Crucially, never give aspirin to children or teenagers due to the risk of Reye syndrome, a rare but serious condition affecting the liver and brain. Always use medications as directed and check with your doctor or pharmacist if you have questions.

- Humidifier/Steam: Using a cool-mist humidifier, particularly in the bedroom, or taking warm showers or baths can help soothe irritated airways and loosen mucus.

- Cough Management: This requires careful consideration. Coughing is your body’s natural reflex to clear infection and mucus from the lungs. While a persistent, hacking cough can be very disruptive (especially to sleep), completely suppressing it might not always be beneficial. Throat lozenges or hard candies can soothe irritation. Honey (for individuals over one year of age) has shown some benefit for cough. If the cough is severe or significantly impacting your quality of life, discuss options with your doctor; prescription medications might be considered in some cases, but over-the-counter expectorants (like guaifenesin) have variable effectiveness.

Will Walking Pneumonia Go Away Without Antibiotics?

If the pneumonia is caused by a virus, it will resolve on its own with time and supportive care, as antibiotics are ineffective against viruses. If it’s caused by bacteria like Mycoplasma, some very mild cases might eventually get better without antibiotics. However, recovery will likely take significantly longer, symptoms may be more prolonged, and there’s a potential (though lower than with classic pneumonia) risk of complications. Given that antibiotics can speed recovery, reduce the duration of contagiousness, and decrease the likelihood of complications in bacterial cases, they are generally recommended when a bacterial cause is strongly suspected or confirmed. Leaving bacterial pneumonia untreated is generally not advised. Always consult with a healthcare provider for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan.

Recovery and Outlook

With appropriate treatment (antibiotics for bacterial cases, supportive care for viral ones), most people with walking pneumonia start to feel significantly better within a few days to a week or two.

However, be patient during your recovery – the cough can linger for a surprisingly long time, often persisting for 4 to 6 weeks, sometimes even longer, after other symptoms like fever and fatigue have cleared. Fatigue can also take a while to fully resolve, so don’t be surprised if you need extra rest for a period.

The overall outlook (prognosis) for walking pneumonia is generally very good. Most people recover fully without lasting effects. Complications are uncommon but can include worsening pneumonia requiring more intensive treatment, ear infections, skin rashes, or anemia. Rarely, in susceptible individuals or those with underlying health conditions, more severe neurological or cardiac complications have been reported.

Prevention: Reducing Your Risk

While there isn’t a specific vaccine available for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, you can take several effective, common-sense steps to reduce your risk of contracting and spreading walking pneumonia and other respiratory infections:

- Hand Hygiene: This is paramount. Wash your hands frequently and thoroughly with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. If soap and water aren’t readily available, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer containing at least 60% alcohol.

- Cover Coughs and Sneezes: Practice good respiratory etiquette. Use a tissue to cover your mouth and nose when you cough or sneeze, and dispose of the tissue immediately. If a tissue isn’t available, cough or sneeze into your upper sleeve or elbow, not your hands.

- Avoid Close Contact with Sick Individuals: If possible, try to limit close contact (like hugging, kissing, or sharing utensils) with people who are showing signs of respiratory illness.

- Don’t Share Personal Items: Avoid sharing drinking glasses, eating utensils, towels, toothbrushes, etc., especially during cold and flu season.

- Stay Home When Sick: This is crucial for preventing spread. If you have symptoms of a respiratory infection, especially a fever or persistent cough, stay home from work, school, and social gatherings until you’re feeling better and no longer contagious (your doctor can advise on this). Even with “walking” pneumonia, resting at home, particularly during the initial days of antibiotic treatment (if bacterial), is wise.

- Don’t Smoke: Smoking significantly damages your lungs’ natural defenses, making you more susceptible to infections. Avoiding secondhand smoke is also important. If you smoke, quitting is one of the best things you can do for your respiratory health.

- Support Your Immune System: Maintain a healthy lifestyle through balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, adequate sleep, and stress management. These habits help keep your immune system strong.

- Vaccinations: While not specific for Mycoplasma, staying up-to-date on recommended vaccinations, such as the annual influenza (flu) vaccine and pneumococcal vaccines (for eligible individuals based on age or health conditions), helps prevent other serious respiratory illnesses. Preventing these infections reduces your overall risk and potential strain on your immune system.

When to Consult with a Healthcare Professional

You should contact your doctor or seek further medical care promptly if:

- Your symptoms worsen significantly (e.g., developing a high fever, experiencing shortness of breath even at rest, confusion, or sharp chest pain).

- Your symptoms don’t start to improve after several days of antibiotic treatment (if one was prescribed).

- You develop new or concerning symptoms not initially present.

- You have difficulty breathing, feel dizzy, or your lips or fingertips appear bluish.

- You have underlying health conditions (like heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, or a weakened immune system) that could put you at higher risk for complications.

Walking pneumonia, while often milder than other forms, is a genuine lung infection that warrants respect and proper care. Recognizing the potential signs, understanding how it spreads, and seeking timely medical evaluation for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan are essential. Don’t hesitate to reach out to your healthcare provider if you suspect you or a family member might have it – we are here to help you breathe easier and get fully back on your feet.